Article: Tuesday, 30 June 2020

In attempts to contain pandemics such as Covid-19 disease, policy makers trade off public health against economic costs (Zingales, 2020). Yet little is known about how effective any containment policies are, and whether such measures are better organised in a centralised or decentralised way. The challenges of exiting from restrictions imposed during the current Covid-19 crisis, as well as the risk of a potential ‘second wave’, underline the urgency of understanding and quantifying the effects of containment measures. In a recent paper, Dr. Dion Bongaerts, Francesco Mazzola and Prof. Wolf Wagner from Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University (RSM) studied the effects of business shutdowns on deaths from Covid-19 in Italy.

In March 2020, Italy was the first country in Europe to completely shut down a selected number of sectors in its economy. On 11 March, the Italian Prime Minister imposed a nationwide shutdown of all food, retail and personal service activities, except for first-necessity goods. Only businesses like supermarkets, small grocery shops, pharmacies, and newsstands were allowed to remain open. In addition to the closing of all other businesses, the decree also drastically limited personal mobility. Two weeks later, the duration of the shutdown was extended and the list of sectors included in the shutdown was enlarged.

From data on local employment structure, the researchers found that about 17 per cent of the economy was shut down on 11 March. If the policies proved to be effective, Italy expected Covid-19 death rates to start declining 10 days after this date because of the virus’ incubation period and other factors (see Lauer et al, 2020).

Although the shutdown policy was centralised, it affected municipalities differently because of a greater or lesser number of businesses in the sectors subjected to compulsory closure. Comparing municipalities with high rates of business shutdowns to those with low rates is called a difference-in-difference analysis, and allows to isolate the effect of the shutdown from other nationwide developments.

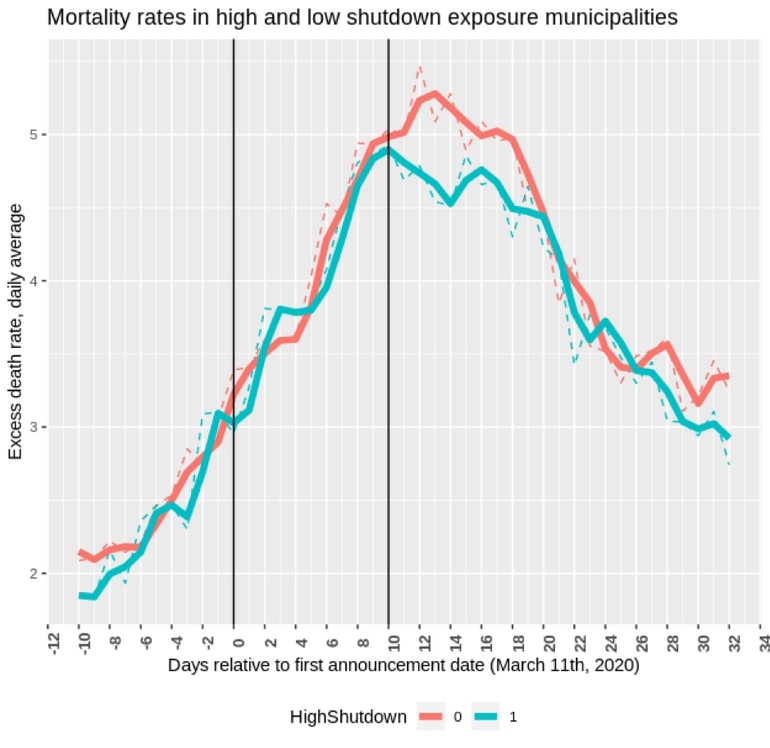

The results of this analysis suggest that business shutdowns are effective in saving human lives: municipalities more exposed to shutdowns experienced subsequently lower mortality rates. The virus did not reach every municipality simultaneously, so the graph of mortality rates (below) shows municipalities grouped according to the week that the virus arrived in the local population. The chart plots the average daily Covid-19 death rate per 100,000 people for municipalities above and below the median shutdown exposure of each group. Specifically, the group of municipalities less exposed to shutdowns is represented by the red line, while the blue line depicts those more exposed to business closures.

The graph shows that about 10 days after the date of shutdown, mortality rates start to decline – and the decline is more pronounced in municipalities that are more exposed to shutdowns compared with municipalities that are less exposed.The analysis enabled the researchers to calculate that the first shutdown saved more than 9,000 lives over 23 days.

This result generally implies that there’s a large societal benefit to be gained from closing businesses during a pandemic. The researchers calculated that the first shutdown could be valued at more than € 9 billion saved.

Assuming that the average residual life expectancy of people who had died from coronavirus would have been another 13 years (the length of time they would have lived if they hadn’t contracted the disease) and the value of a statistical Life-Year to be about € 80,000 a year (Stadhouders et al., 2019).

The researchers’ analysis also shows that business shutdowns have important spillover effects. Business closures may limit the spread of the virus outside a municipality because there are fewer commuters (as well there being general travel restrictions during the sample period).

The researchers found that shutdowns in centres of business consistently reduced mortality rates in neighbouring municipalities. The beneficial effect was large – in fact it was comparable to the effect of a municipalities' own shutdown. Beck and Wagner (2020) also found beneficial geographical spillover effects. They concluded that countries should co-ordinate containment policies such as shutdowns to prevent people crossing borders for any reason; cross border travel has the potential to spread disease further.

The beneficial spillover effects of shutdowns aren’t just for commuting or working populations either; there’s also a big effect on people who are very unlikely to be in work, such as the elderly. This points to significant contagion effects that reach beyond economically active businesses and organisations, say the researchers.

In general, the existence of spillover effects points to the benefit of centralising or co-ordinating shutdown decisions.

Finally, the analysis further points at rapidly declining benefits to scale from sectoral shutdowns. Results suggest that the effectiveness in municipalities with the lowest sector exposure is more than three times higher than the average effectiveness across all municipalities. In addition, estimates suggest that these benefits are relatively more pronounced in the retail sector, because shutting down this sector contributes most to the decline in mortality rates – and because online shopping, and ordering deliveries from local suppliers provides an obvious alternative.

Ultimately, the results found by Dr Bongaerts, Mazzola and Prof. Wagner are consistent with a lower effectiveness of a second shutdown, suggesting large benefits from targeted – rather than widespread – business closures.

The paper has been published in PLoS ONE under the title "Closed for business: The mortality impact of business closures during the Covid-19 pandemic"

RSM offers Executive Education and Master programmes in various business areas for any stage of your career. For instance:

Science Communication and Media Officer

Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University (RSM) is one of Europe’s top-ranked business schools. RSM provides ground-breaking research and education furthering excellence in all aspects of management and is based in the international port city of Rotterdam – a vital nexus of business, logistics and trade. RSM’s primary focus is on developing business leaders with international careers who can become a force for positive change by carrying their innovative mindset into a sustainable future. Our first-class range of bachelor, master, MBA, PhD and executive programmes encourage them to become to become critical, creative, caring and collaborative thinkers and doers. www.rsm.nl

For more information about RSM or this article, please contact Danielle Baan, Media Officer for RSM, via +31 10 408 2028 or baan@rsm.nl.